Did you know there are 24 Korean seasons?

There’s a longstanding joke among foreigners that live in Korea that pertains to how it is so often promoted that Korea has four distinct seasons. It is as if people, or perhaps the Korean tourism organization, think it is quite unique to have four seasons. As someone who grew up in Ohio in the US, I never really got all the four-season hubbub.

I think the joke also plays off of how dreadfully hot, humid, and long summer in Korea can feel and how frigid and cold and long winter in Korea can feel and between them the delightful, but short, cherry blossom-filled spring in Korea, and the brisk pace of autumn in Korea. Summer and winter can feel so long and the other two seasons so short that some years, it doesn’t feel like there are four seasons in Korea at all. And so they remind us, there are 4 seasons in Korea!

What Korea should really be promoting, and what would be truly unique, is that on the traditional annual calendar, Korea actually has 24 seasons! Now that’s something to brag about I think!

Here’s what to know about the 24 Korean seasons:

- The Jeolgi Calendar

- The Essence of Jeolgi

- A Calendar Rooted in Agriculture

- Festivities and Folklore

- The 24 Seasons Of Korea

- Jeolgi in Modern Korea

(This post contains affiliate links, which means I receive a certain percentage of a sale if you purchase after clicking at no cost to you. Thank you for your support.)

The Jeolgi Calendar

The Korean Lunar Calendar has 24 distinct seasons known as jeolgi which offer a fascinating glimpse into the connection with nature and agriculture. Once you know about it, you can’t not see how so many of the traditions ebb and flow along this calendar as well.

If you visit the National Folk Museum of Korea in Seoul, you can walk through each season learning about the different celebrations, food to eat, and traditions that pertain to each. It’s so interesting and if you’ve lived in Korea for a few years, understanding these seasons will help you understand why certain foods are served at certain times and why certain festivals take place annually.

You will be that much more connected with the people and Korean culture when you understand the jeolgi calendar.

The Essence of Jeolgi

The concept of jeolgi, which means “turning points of the season,” is a system that divides the year into twenty-four specific periods, each lasting approximately 15 days. This division is based not just on the lunar phases, as one might initially think, but also incorporates solar terms to mark significant changes in weather, climate, and agricultural timelines.

Originating from the Zhou Dynasty in China over 3,000 years ago, and adopted by Korean farmers 2,000 years ago, the jeolgi system reflects an understanding of the natural world and its cycles.

A Calendar Rooted in Agriculture

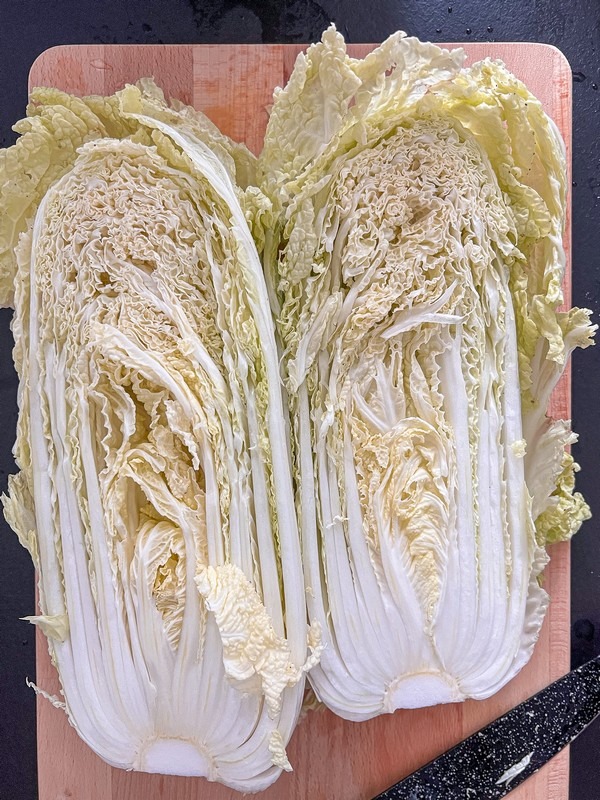

Agriculture has long been the backbone of Korean industry and life, with the success of crops playing a crucial role in the survival and prosperity of its people. You’ll find that still today, the crop outcome still heavily effects life in Korea. If the monsoon rains are too long, the cabbage yield is lower which effects the kimjang making in the autumn and so on.

The jeolgi calendar served as an essential guide for farmers, dictating when to sow, plant, and harvest, based on the nuanced changes in weather that each season brought. By closely observing and aligning their agricultural practices with the jeolgi, Korean farmers could maximize their yields and ensure the sustenance of their communities.

Festivities and Folklore

Many of Korea’s traditional festivals and holidays are intricately linked with the lunar calendar and the jeolgi so even if you don’t think you know much about the jeolgi, you might actually know more than you realize.

Celebrations such as Seollal, the Lunar New Year, Jaewol Daeboreum, the first full moon, Chuseok, or the Korean Thanksgiving, and Buddha’s Birthday, are all observed according to the lunar calendar, each carrying its own set of customs and significance rooted in the Jeolgi system.

The 24 Seasons of Korea

The cycle begins with Ipchun, marking the start of spring, and progresses through each season, reflecting the natural ebb and flow of life. From the cold snap of Sohan, or Small Cold, to the deep chill of Daehan, or Great Cold, each Jeolgi season carries its own character and implications for daily life and agriculture.

For instance, the arrival of Ipha signals the beginning of summer and the time for tending to crops and silkworms, while Ipdong denotes the onset of winter and the preparation for kimjang, the traditional making of kimchi.

Spring

The frozen ground melts and everything begins to sprout. It’s the sowing season and the starting point for farming and fishing in Korea.

Ipchun (입춘) – The Beginning of Spring

Starting around February 4, Ipchun signals the time to start plowing the fields in preparation for farming.

Each household would traditionally post an Ipchunchuk on their front gate or doorpost to bring blessings. The Ipchunchuk is a rectangular sign hung above doorways to attract good luck. The paper on which Ipchunchuk is written varies in the number of characters and size, but it is common to use two sheets of hanji that are about 15 centimeters wide and 70 centimeters long.

In fishing villages, people begin fishing after performing specific shamanistic rites on Yeongdeungnal, Wind God’s Day, to seek blessings for a fruitful catch.

What to write on your Ipchunchuk:

- “May the wind and rain be in harmony, and may the years be fruitful.” – 우순풍조 시화년풍 (雨順風調 時和年豊)

- “May a thousand calamities pass away and a hundred blessings come.” – 거천재 내백복 (去千災 來百福)

- “May longevity be like a mountain and prosperity like the sea” – 수여산 부여해 (壽如山 富如海)

Usu (우수) – Start of the Spring Rain

Starting around February 19, the cold winter has passed, and spring has arrived. The literal meaning is “rain water” and refers to the transition when the snow changes into rain because of the warmer temperatures.

This period marks the beginning of hibernating frogs waking up and falls 15 days after Ipchun. With this, spring is in full swing, bringing warmth and renewal to the country.

Traditional holidays during this period:

Seollal (설날): The Lunar New Year is celebrated with a bowl of tteokguk, or rice cake soup and families traditionally partake in jesa and do the New Year’s bow, or sebae.

Jeongwol Daeboreum (대보름): The Great Full Moon Festival is the time to wish for the year’s abundance and peace. Each village would traditionally hold a dongje and the people play a tug-of-war called juldarigi and make wishes for the first full moon of the year. Traditional games like yut nori are played as well.

Gyeongchip (경칩) – Insects and Creatures Awake from Hibernation

Starting around March 5, the 74th day after Dongji, or the winter solstice, it’s time to start working the land, building fences, and mending walls. On this day, people observe how the barley is growing to predict the year’s harvest.

People may also cut down maple trees and drink their sap, believed to be effective for stomach ailments and internal diseases. The maple sap collected from Songgwangsa Temple and Seonamsa Temple in Gurye, Jeollanam-do is particularly famous.

Trees usually start to swell around the spring equinox, but in the southern regions, this happens a bit earlier. People aim to harness the new energy of the year through the first sap. Maple sap flows best in clear weather and is less effective or even absent when it’s cloudy or windy. After Gyeongchip, sap flow decreases and loses its medicinal potency.

Gyeongchip marks a time when all things come to life, reviving new vitality after a long winter.

Chunboon (춘분) – Days Begin to get Longer

Starting around March 21, Chunbun, meaning “the center of spring” or the spring equinox, marks a time when day and night are of equal lengths. On this day, yin and yang balance perfectly, making the lengths of day and night, as well as the cold and heat, equal.

The weather on this day was traditionally used to predict the year’s harvests and droughts. For instance, if it rains on the vernal equinox, it is said there will be fewer illnesses. It’s considered favorable if the day is dark and the sun is hidden.

If blue clouds appear in the east at sunrise, it bodes well for barley and promises a good harvest. Conversely, a clear, cloudless day suggests poor growth and many diseases. The color of the clouds on this day also carries meaning: blue indicates insect damage, red signals drought, black warns of floods, and yellow foretells a good harvest.

Traditional holidays during this period:

Yeongdeungnal (영등날): Wind God’s Day is considered the beginning of spring. The first day of the second lunar month when the goddess Yeongdeung Halmeoni, who governs the wind that has a great influence on industries such as farming and fishing, comes down from heaven to the human world.

Chungmyung (청명) – The Sky Becomes Clearer

Starting around April 5, Cheongmyung, which literally means “a day with good weather,” marks a time when the pleasant weather makes farming and fishing easier as spring begins. Cheongmyung often coincides with Hansik, leading to some confusion between the two. Even today, they are passed down without a clear distinction.

Traditionally, this was the time when the king’s servants would start a fire by rubbing a willow branch against an elm trunk and then offer the flame to the king. The king would then hand out torches made from this flame to 360 towns across the country. This was the “new fire” that would replace the “old fire”.

Gokwoo (곡우) – Grain Rain

Starting around April 20, this period marks when the grains awaken. It’s said that croakers don’t start their chorus until Gokwoo passes. Around Gokwoo, the farming season begins with the preparation of seedbeds. There are many sayings that go along with this period when farming is really underway.

Sayings include:

- All crops wake up on Gogu.

- Expect a drought if the weather is dry on Gogu day.

- A rainy Gogu is not good for crops.

Fun Fact: In Pyeongchang, Gangwon-do, they soak rice seeds at the hour of the snake on Gokwoo Day to prevent them from floating away. After soaking the seeds, they tie a gold rope around the jar and hold a ritual. This practice aims to protect the seedbed from frogs or birds that might ruin it. They also prepare rice on the night of the soaking and hold a simple ritual to ensure a bountiful season.

Traditional holidays during this period:

Samjidnal (삼짇날): Known as the Day of the Swallows or Double Three Day, falling on the third day of the third lunar month, this time marks the arrival of the spring breeze and blooming blossoms. It’s a season to embrace flowers and enjoy fresh spring namul, or wild vegetables.

Legend has it that seeing a white butterfly on this day foretells mourning clothes for the year, while spotting a yellow or tiger butterfly promises good luck.

On this day, households prepare and enjoy various kinds of spring rice cakes. They pick azalea flowers, mix them with glutinous rice flour, spread sesame oil on them, and fry them into round shapes, creating a delightful treat called hwajeon.

Hansik (한식): Cold Food Day is a time to hold ancestral rites at graves, showing gratitude to ancestors, and to eat only cold food. According to the Cheongmyeongjo of the Dongguk Sesigi, on this day, willow and elm trees were rubbed together to create new fire, which was then offered to the king.

The king distributed this fire to the prime minister, ministers, civil and military officials, and the magistrates of the 360 districts in a ritual called ‘sahwa.’ The magistrates then distributed this fire to the people on Hansik. Because they had to wait for the new fire to be made after extinguishing the old fire, they couldn’t cook rice and thus ate cold rice, giving the day its name, Hansik.

Summer

The season with lots of sunlight and rain and crops reaching their full potential. It is the busiest season for farmers with the most important work being rice planting and weeding. Rural villages organize dure, or a farmers’ cooperative group, to ensure that all of the work is finished in time.

Ipha (입하) – Start of Summer

Starting around May 6, during the fourth lunar month, Ipha marks the beginning of summer according to the lunar calendar. By this time, spring has completely faded, mountains and fields are turning green, and the croaking of frogs fills the air. In the yard, earthworms wriggle, while melon flowers begin to bloom in the fields.

Rice seeds are sprouting in the seedbeds, and barley heads are starting to emerge. At home, women are busy raising silkworms, while in the fields, pests are increasing, and weeds are growing, making it a challenge to keep them under control.

Soman (소만) – Grain Growth

Starting around May 21, people begin picking mugwort leaves to eat as greens. The cold greens have disappeared, and the barley ears are ripening and turning yellow, signaling the start of summer.

There’s a proverb that goes, “The cold wind blowing around this time of year makes an old man freeze to death.” Breezes around this time can be unexpectedly cool or frigid, so it’s best to be ready.

Mangjong (망종) – Grain in Ear, or Bearded Grain

Starting around June 6, there’s a saying, “Barley must be cut before Mangjong.” This means barley should be harvested before Mangjong to allow for rice planting and plowing. Barley often falls over in the wind after Mangjong, so the saying also serves as a caution.

Mangjong is also the time when grasshoppers and fireflies start to appear, and plum trees begin to bear fruit. In the southern region, where barley farming is abundant, this period is particularly busy. It’s the peak of the agricultural season, leading to the saying, “I’m peeing on my feet (발등에 오줌 싼다),” reflecting the non-stop activity and continuous rains as farmers prepare for rice planting.

Haji (하지) – Summer Solstice

Starting around June 22, Haji, or the summer solstice, marks the longest day of the year when the sun is at its northernmost point in the sky. It is one of the most important days of the summer season.

This period is exceptionally busy as preparations for the rainy season and drought are underway. Tasks include buckwheat sowing, silkworm breeding, potato harvesting, pepper field weeding, garlic harvesting and drying, barley harvesting and threshing, rice planting, late soybean planting, hemp harvesting, and pest control. In the southern region, rice planting that began around Dano concludes around the summer solstice, marking the start of the rainy season.

Traditional holiday during this time:

Dano (단오): Falling on the fifth day of the fifth month, Dano is a festival where people exchange Dano fans, believed to carry the greatest yang (positive) energy of the year. Traditionally, people wash their hair in Korean iris water, known as changpo, and wear cool ramie jackets and skirts.

Gangneung Danoje Festival: Some cities still celebrate with large festivals, and Gangneung hosts one of the largest and most famous festivals for Dano in the country. If you want to celebrate, this is the place to visit.

Soseo (소서) – Weather Begins to get Hotter

Starting around July 5, this period marks the summer monsoon season, with the monsoon front lingering over the central part of the Korean peninsula. This results in high humidity and frequent rains.

Traditionally, this was when the rice seedlings planted around the summer solstice began to take root, and farmers would plant rice fields 20 days after the initial planting.

Daeseo (대서) – Full Summer Weather Begins

Starting around July 23, this period marks the middle of summer, when the rainy season ends and the heat is at its peak. Daeseo often coincides with the midsummer heat, leading to the tradition of preparing food and drink and heading to valleys or mountaintops to escape the three hottest days of the year called Sambok.

Traditional holidays during this time:

Yudu (유두): A water festival held in the sixth lunar month was a day for people to visit rivers and streams to cool off. Today, it’s when people plan their summer vacations.

Sambok (삼복): The three hottest days of the summer and it is on these days that people should eat rejuvenating foods like samgeytang, or chicken soup.

Autumn

The season for harvesting the crops sown in the spring and summer, farmers busy themselves cutting, threshing, and storing rice.

Ipchoo (입추) – Start of Fall

Starting around August 8, Ipchu marks the official beginning of autumn in Korea and is the thirteenth of the twenty-four Jeolgi. Though late summer heat waves still occur, cool breezes begin to blow at night, signaling the start of preparations for autumn.

Farmers used to predict the harvest based on the weather on Ipchu. If it was clear, they believed that the harvest would be abundant; if the forecast called for heavy rain, it was seen as a sign of impending crop failure.

Radish and cabbage for kimchi are planted during this time. Weeding is completed, and the countryside begins to quiet down.

Cheoseo (처서) – Summer Heat Begins to Lessen

Starting around August 23, after the summer solstice, the scorching sun eases and the grass stops growing. During this time, the grass on the ridges of the rice fields is cut or weeded to ensure proper oxygen flow. The weather around Cheoseo should be pleasant and the sun rays strong enough for the rice to mature fully.

In the past, women and scholars would take this opportunity to dry clothes and books that got wet during the rainy season, either in the shade (eumgeon) or in the sun (posae).

Traditional holiday during this time:

Chilseok (칠석): Chilseok is the day when the legendary Cowherd and Weaver Girl meet. According to the legend, Altair (the Cowherd) and Vega (the Weaver Girl) on either side of the Milky Way meet once a year on this evening. They are said to have whispered love to each other and incurred the wrath of the Jade Emperor, who separated them, allowing them to meet only once a year on the night before Chilseok. Magpies and crows spread their wings to form Ojakgyo, the bridge they cross.

Around Chilseok, the heat eases slightly, and the rainy season can be intense. The rain during this time is called Chilseokmul (Chilseok water). Pumpkins ripen well, and cucumbers and melons are plentiful. People make pumpkin pancakes and pray to Chilseong during this period.

Baekro (백로) – White Dew Period

Starting around September 9, Baekro, or the ‘white dew’ period, gets its name from the little drops of dew that appear on the ground in the mornings. The wild geese return home and the swallows begin their southward journey.

Chooboon (추분) – Autumn Equinox

Starting around September 23, the autumnal equinox marks the day when day and night are equal in length. This turning point in the season sees the disappearance of lightning, bugs hiding underground, and water beginning to dry up. It’s also the time when typhoons often blow.

During the autumn equinox, grains are harvested from the fields, cotton is picked, and peppers are picked and dried. Other autumn harvest tasks include gathering pumpkin leaves, gourd leaves, perilla leaves, and sweet potato sprouts. Wild vegetables are dried to prepare fermented vegetables for the coming months.

Traditional holiday during this time:

Chuseok (추석): The Korean Thanksgiving is one of the biggest holidays of the year for Koreans. Traditionally, Koreans would head back to their family homes in the villages or towns that they came from, dress in traditional Hanboks and wake very early to hold an ancestral rite to pay respects to the ancestors that came before them.

Hanro (한로) – Cold Dew Period

Starting around October 8, Hanro marks the beginning of the cold season. As cold dew begins to form, the harvest must be completed before temperatures drop further. In rural areas, threshing is in full swing to gather all five grains and various fruits. Autumn foliage, more beautiful than summer flowers, deepens in color, and summer birds like swallows give way to winter birds like geese.

During this cold and frosty season, commoners enjoyed loach soup as a seasonal food. Loach, known for stimulating yang energy, gets its name because it becomes fat and yellow in the fall, making it a favored autumn fish.

Sanggang (상강) – Arrival of the Frost

Starting around October 23, autumn’s clear weather persists, but nighttime temperatures drop significantly. Water vapor condenses on the ground, forming frost, and as it gets colder, the first ice appears.

This late autumn season showcases the peak of maple leaves and the full bloom of chrysanthemums. Autumn outings, often accompanied by drinking chrysanthemum wine like on Jungguil, are closely tied to this beautiful and crisp seasonal change.

Traditional holiday during this time:

Jungyangjeol (중양절): A celebration of autumn with poetry and painting on the ninth day of the ninth month of the lunar calendar. People gather to eat chrysanthemum pancakes or gukhwajeon (국화전) and honey citron tea, or yuja cheong (유자청).

Winter

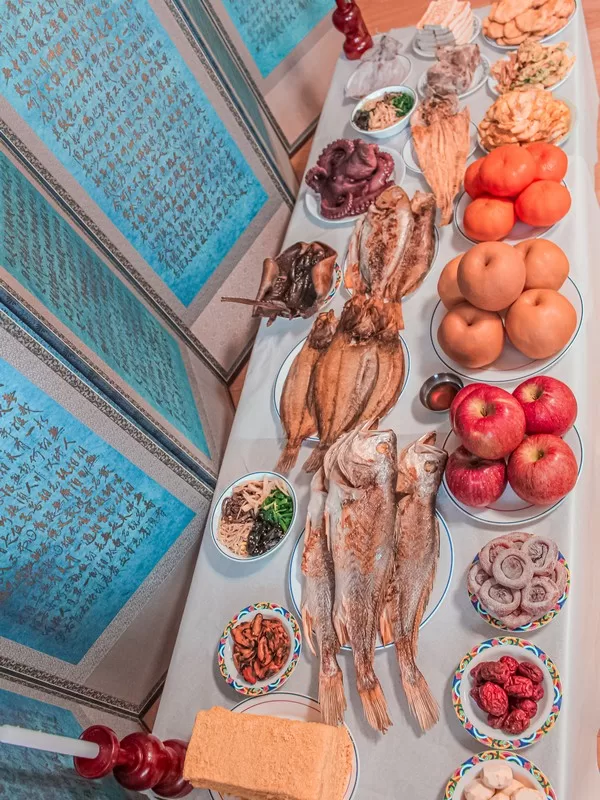

The season of snowy fields and biting cold, farmers prepare for the new year by getting firewood, repairing farming tools, and resting. Fishermen are quite busy during this time cultivating oysters or laver, seaweed, and catching skate and pollack.

Ipdong (입동) – Start of Winter

Starting around November 7, Ipdong means ‘onset of Winter’, and represents the beginning of the coldest and harshest period of the year. At this time, families start to prepare for kimjang, or the making of kimchi which will last through the winter months.

Kimjang traditionally took place within the five days before or after the beginning of Ipdong, as this was thought to be the time when it would become most delicious. If you want to partake in the annual kimjang festivities, be sure to note this date down. That said, because of global warming, the dates for kimjang seem to be getting pushed back a little by little each year.

Soseol (소설) – Little Snow

Starting around November 22, the weather turns cold enough for snow to fall. Although the farming season has passed, there are still tasks to complete before winter sets in: tie and hang dried radish greens, slice and dry radish greens or pumpkins, and pick and care for cotton. Additionally, rice straw is collected to use as cattle feed throughout the winter.

Traditionally, this was not a seasonal holiday but a day that signaled the beginning of winter preparations.

Daesol (대설) – Major Snow

Starting around December 7, this period marks the middle of winter. Farming slows down, and the grains harvested during the fall are now stored in granaries, ensuring that there’s no need to worry about food for the time being.

Dongji (동지) – Winter Solstice

The winter solstice is celebrated on the day of the year with the shortest daylight hours and the longest night and it usually falls on or around December 22nd each year. From Dongji, the days start to get longer leading up to spring which is often seen as the new year in many places as that’s when things start to bloom, babies are born and all of the new things of the year pop up, out and whichever other way. This was also the day when, historically, the kings of Korea would hand out the calendar for the upcoming year.

In the past, families gathered to perform the ancestral rites before eating their patjuk (팥죽) and placed a bowl of the dark lumpy dish in each room of the house to ward off evil spirits. While most families don’t do this anymore, many people still follow the custom of eating a big heaping bowl of patjuk, or red bean porridge, to mark the coming of the new year.

Sohan (소한) – Small Cold

Starting around January 5, sohan means ‘small cold’ and it was thought to be the coldest day of the year in Korea. After Sohan, the weather gets progressively colder, before snapping and beginning to ease over the following period called Daehan.

Magpies build their nests and the pheasants cry. In snowier regions, people stock up on firewood and food in preparation for the sudden and heavy snows to come.

Daehan (대한) – Great Cold

Starting around January 20, Daehan falls on the last day of the lunar calendar. The coldest period of the year continues. One of the old sayings at this time: “If it is not cold, it’s not Sohan; if it is not mild, it’s not Daehan, ” or “The ice of Sohan melts on Daehan.”

Traditional holidays during this time:

Nabil (납일): A day when the people or the government held memorial services for their ancestors, ancestral shrines, or shrines.

Seotdal Geumeum (섣달그믐): The last day of the lunar year, so people would traditionally stay up until the rooster crows at dawn to welcome the new year.

Jeolgi in Modern Korea

Although the direct reliance on the jeolgi calendar for agriculture has diminished in modern times, its influence persists in the cultural and spiritual life of Korea and the more you know about it, the more you’ll notice its effect on life in Korea.

When I worked at the public school, I could clearly see how it ebbed and flowed as we would get certain foods at very specific times. The jeolgi seasons are still the basis for various festivals, culinary traditions, and rituals in Korea, so the more you know about them, the more you’ll be able to partake and celebrate in life in Korea.

If you like learning about Korean traditions and culture, I’m sure you’d find this just as fascinating as I did. Now that you know, follow the signs of the seasons and make sure to eat what you need to eat on the right days of the year.

Did you like this post? Pin IT!