Traditional Korean Masks: Ancient Faces with Sacred Stories

Last Updated on May 2, 2025

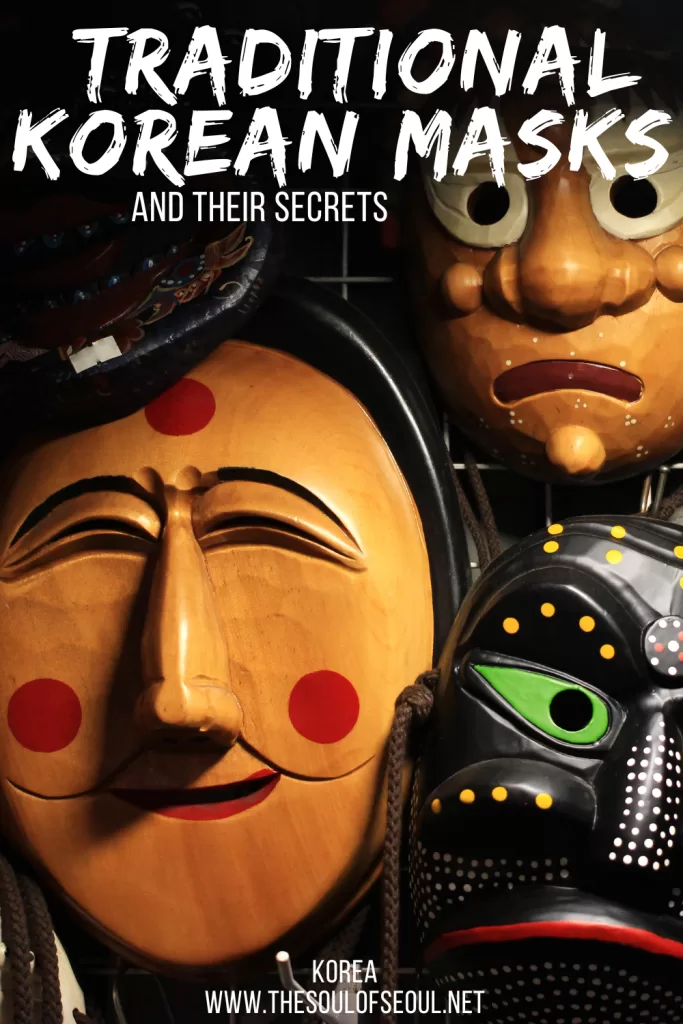

You’ve seen Halloween masks and masquerade masks. But in Korea, masks, or tal (탈), are something else entirely. They’re sacred. Part performance, part prayer, and all symbolism, traditional Korean masks are intriguing, unique, and you can spot them more places in Korea than you might realize, from the streets of Insadong to performance venues around the country. They’re still worn, still revered, and still relevant to Korean culture.

Want to know what these faces mean and the stories they have to tell? It’s time to learn about the traditional masks in Korea.

Get ready to learn about Korean traditional masks from the common sights and the rarest of them all:

- What is a mask? What is a tal?

- Talchum: Where Spirit Meets Satire

- The Legend of Cheoyong: A Mask That Protects

- Hahoetal: The Masks You Might Recognize

- Other Sacred Masks of Korea

- The Materials Are Just As Important

- See the Tradition Come Alive

(This post contains affiliate links, which means I receive a certain percentage of a sale if you purchase after clicking at no cost to you. Thank you for your support.)

What is a mask? What is a tal?

The word tal (탈) has two meanings in Korean: it means “mask,” and it also means “misfortune” or “trouble.” That’s not a coincidence.

Historically, masks were believed to absorb bad luck and illness. To keep one in your home was to risk bringing that energy inside. That’s why masks used in ceremonies were usually burned after the performance, or kept locked in a village shrine where no one dared to touch them. They were sacred, and a little dangerous. Which makes it interesting that today many people that visit Korea buy them as souvenirs to take home.

People believed that masks had the power to protect or punish, depending on how they were treated. They weren’t just performance props as many might think as they cursorily watch a traditional performance in Korea. They were spiritual tools, feared and revered.

Talchum: Where Spirit Meets Satire

Masks have been used on the Korean peninsula since prehistoric times, showing up in shamanic rituals, royal court ceremonies, and village festivals long before modern entertainment existed. Commonly used as a way to help humans become something else: a god, a ghost, a lion, a fool, a demon, in Korea, that transformation came to life in the mask dance drama known as talchum (탈춤).

Performed outdoors in village squares, talchum is a rebellious drama. Dancers may wear brightly colored hanbok and expressive wooden masks to act out savage critiques of the elite. They mock corrupt monks, greedy nobles, and lustful scholars. They celebrate fools and concubines. If you can understand Korean, you’ll get in to these dramatic portrayals.

It was one of the few ways commoners could publicly laugh at the powerful. Satire was survival. And it still hits hard. Today, talchum is an official symbol of Korean cultural heritage, recognized for both its artistic and social value.

The Legend of Cheoyong: A Mask That Protects

Few masks are as iconic as the Cheoyong mask (처용탈). Its origin story dates back to the Silla Kingdom (57 B.C.-A.D. 935). Cheoyong, a son of the Dragon King, returned home one night to find a a stranger in bed with his wife. But instead of fighting, he sang and danced:

“With the bright moon in the east, after wandering around all day,

I come back and see four legs in my bed.

Two are surely mine, but whose are these other two?

They used to belong to my wife—but what can I do now?”

Impressed by his nonchalant response, the stranger revealed himself as the “plague spirit”. The demon, stunned by Cheoyong’s grace and humor, vowed never to enter a house bearing Choeyong’s image.

Since then, Koreans began hanging Cheoyong masks on their doors to ward off disease and evil spirits, especially smallpox.

Until the end of the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), the Dance of Cheoyong was performed by a solo dancer as a ritual to ward off evil spirits. In the subsequent Joseon Dynasty, during the reign of King Sejong (r. 1418-1450), the Dance of Cheoyong was combined with the Crane Dance and the Lotus Pedestal Dance, and developed into the current form called the Dance of Cheoyong in the Five Directions, performed by five dancers at banquets or other festive occasions in the royal court and government offices.

Today, the Dance of Cheoyong is still performed, though now as cultural heritage rather than exorcism.

Hahoetal: The Masks You Might Recognize

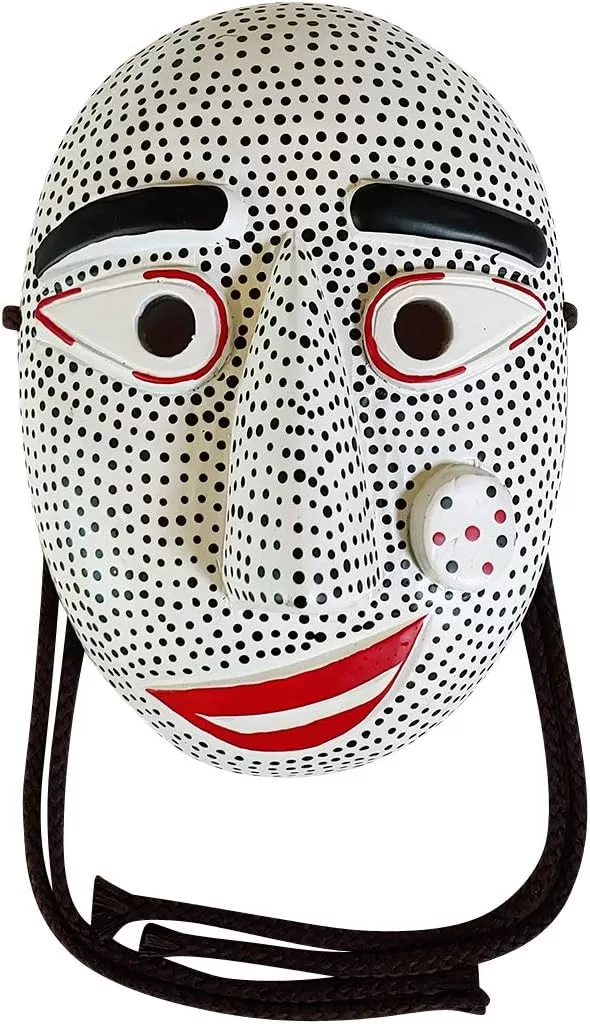

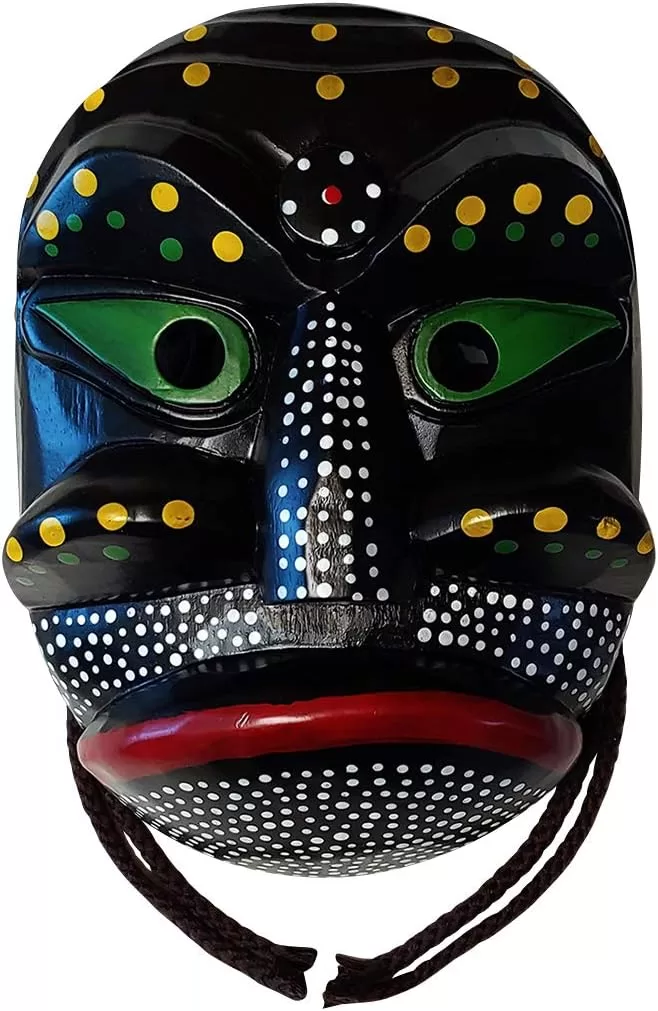

The most famous of Korea’s traditional masks, the ones which most foreigners will find scattered throughout the country at souvenir shops, are the Hahoetal (하회탈), from the village of Hahoe in North Gyeongsang Province.

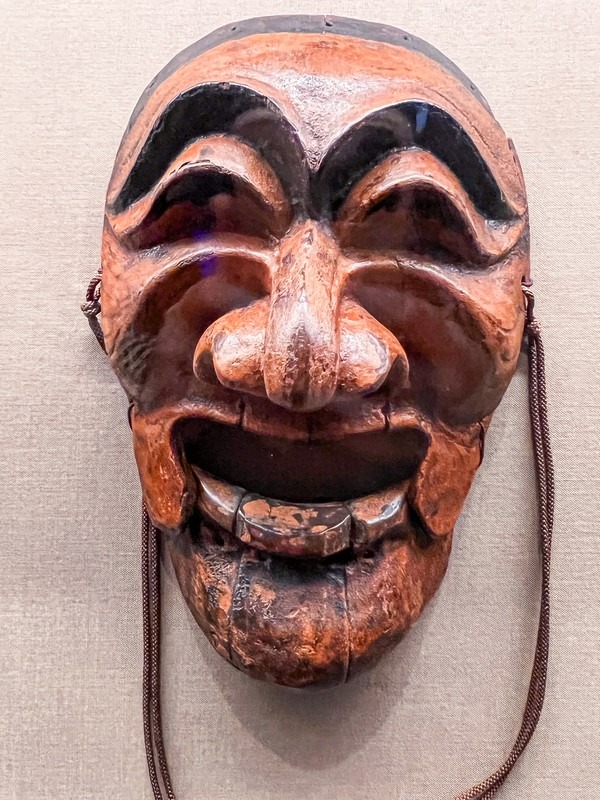

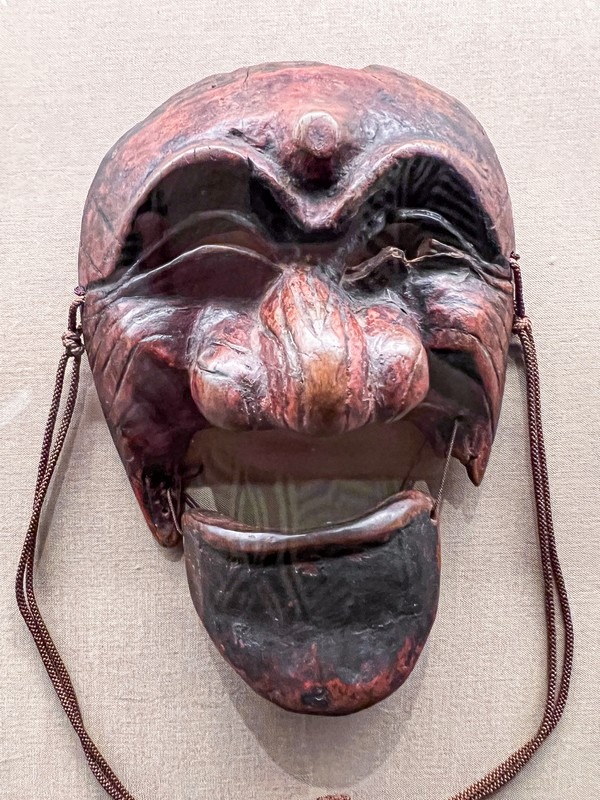

Created during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), these carved wooden masks are full of facial expression and symbolism. Their asymmetry and moving jaws allow dancers to change expressions mid-performance. A tilt of the head and the mask smiles, or the other direction and it sneers.

Fun Fact: The exact origin of Hahoetal is unknown, however, the story goes that a young man received directions in a dream to create the masks in private, allowing no one else to see them. He hung a straw rope around his house so no one else could enter until he finished. However, a girl that was impatient after not seeing her love for many days, poked a hole in his window to see what was going on. When the deities’ found out the rules had been broken, the boy began hemorrhaging and died on the spot. This is why the mask Imae does not have a chin, as he was working on it when he died.

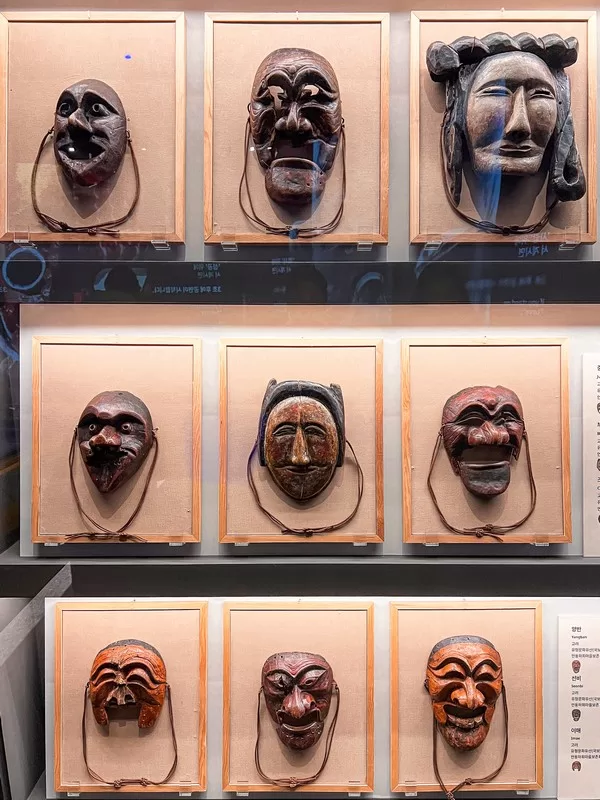

Each Hahoetal represents a stock character in the Hahoe byeolsingut talnori (하회 별신굿 탈놀이), a sacred mask dance drama honoring local deities. Each mask is a carved archetype, designed to critique, laugh, and connect. The full cast includes:

- Halmi (할미): the aged grandmother

- Baekjeong (백정): the mocking butcher

- Gaksi (각시): the shy bride and village goddess

- Choraengi (초랭이): the snarky servant

- Bune (부네): the flirty concubine

- Chung (중): the corrupt monk

- Imae (이매): the fool without a chin

- Seonbi (선비): the pompous scholar

- Yangban (양반): the smug nobleman

Fun Fact: Originally, there were twelve masks, however three have been lost to time so there are only 9 that remain. The three that are lost are Ttoktari (떡다리), an old man, Pyolchae (별채), a tax collector, and Chongkak (총각), a bachelor.

Other Sacred Masks of Korea

Bangsangssi

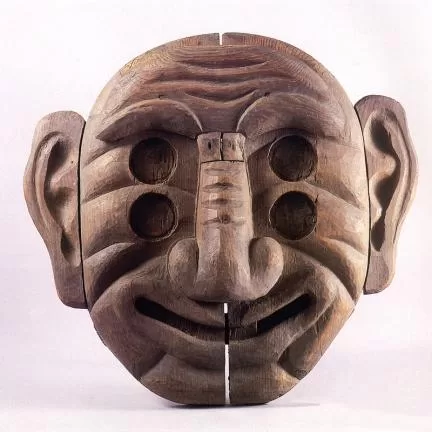

The Bangsangssi is the oldest known mask in Korea, dating back to the 6th century Silla Dynasty. With four eyes, it was meant to see and repel evil spirits during funerals and royal exorcisms. Crafted from pine or straw, it was considered so dangerous after use that it was either buried or burned.

Today, only one Bangsangssi mask from the Joseon era remains, housed in Korea as Important Folklore Material No. 16.

Lion Masks

In ancient Korea, lions were thought to expel evil and bring luck. Lion masks were used in exorcism ceremonies at the beginning of the year. In places like Bukcheong, it was believed that children would live long, healthy lives if they rode the lion’s back during the dance.

Lion masks are still used in Bongsan and Gangnyeong mask dances today, their golden eyes and jingling bells keeping evil at bay with every step. I spotted my own lion mask at the Lotus Lantern Festival in Seoul.

Obangsinjang

Masks representing the gods of five directions, east, west, south, north, and center, were used in a dance to clear all corners of a performance space from spiritual pollution. Each god wears a color: blue, white, red, black, and yellow. This ritual dance still survives in places like Gasan.

Monsters & Spirits

From Yeongno (영노), the monster mask, to twin masks like Nunggeumjeogi (눙금저기) and Yeonnip (연잎), Korean masks often served dual roles: theatrical and exorcistic. In Yangju’s mask dance, these characters punish corrupt monks and serve as symbolic protectors, honored before performances to ensure success and purity.

The Materials Are Just As Important

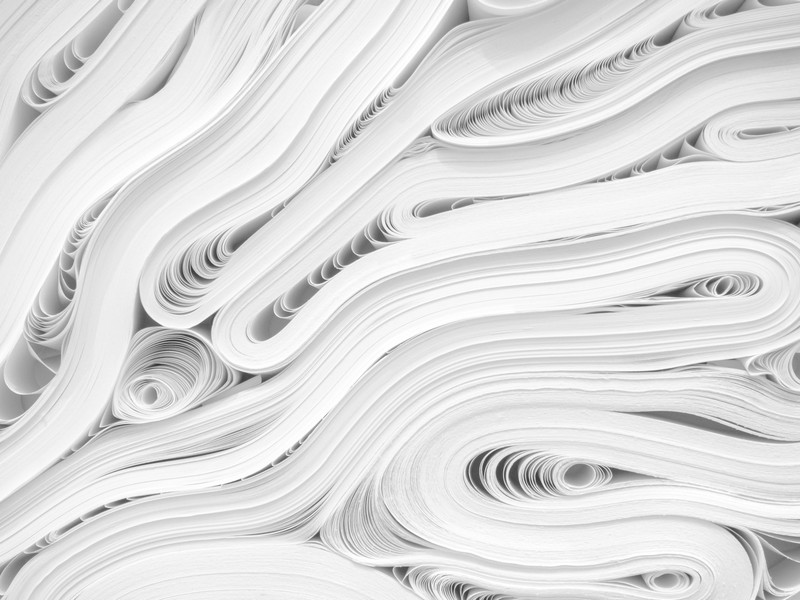

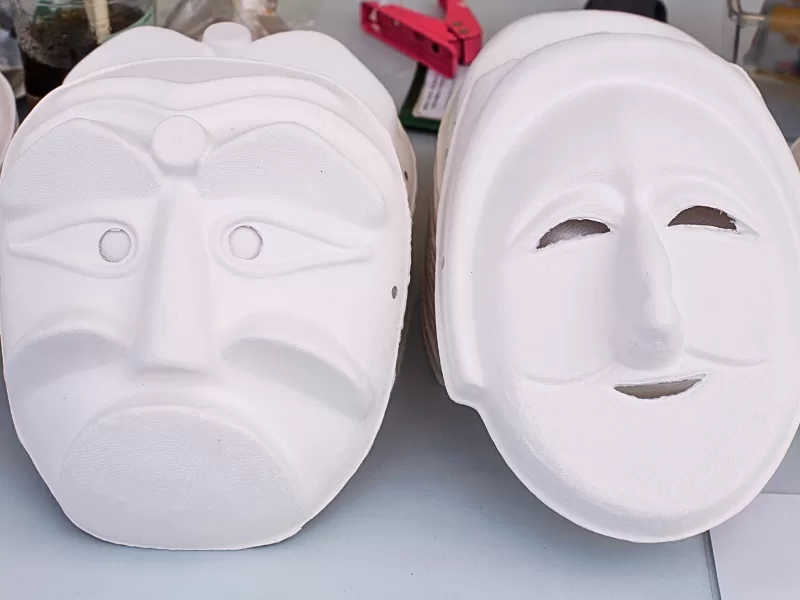

Not all masks are carved from wood. Korea’s traditional masks were made from materials that matched their use and each medium had it’s own meaning or connection to the land:

- Wood: Sacred, durable (used in Hahoetal and Cheoyong)

- Hanji (mulberry paper): Flexible and expressive (used in regional performances)

- Gourds and Straw: Common in folk performances like Ogwangdae (오광대)

- Bamboo: Lightweight and ideal for animal masks like lions

If you’re in Korea, you can stop into just about any stationary shop, or moongu (문구), and find a traditional Korean mask made for decorating. If you’re looking for traditional crafts in Korea, these shops are always a great place to start.

See the Tradition Come Alive

Want to experience Korean mask culture firsthand? Visit Hahoe Village, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, or attend the Andong Mask Dance Festival held every October. From talchum performances that are scheduled daily to mask-making workshops, there is a lot to learn about this particular aspect of Korean culture in Andong, Korea.

Whether made for a funeral or a festival, worn by a shaman or a comedian, the tal remains one of the most powerful symbols of Korea’s cultural soul. The next time you spot one, see if you can remember what it means.

Did you like this post? Pin iT!

One Comment

L

Fascinating! Thank you!

My dad had bright home some souvenir masks from Korea and I always thought they were so cool.