How To Perform A Korean Jesa Ceremony

Last Updated on December 20, 2024

Twice a year, Koreans travel across the country to their family homes to hold jesa. Jesa (제사) ceremonies are performed to honor the ancestors that have come before and paved the way for those that live today and the Lunar New Year is one time during the year that almost everyone partakes in the memorial rite.

Since my Korean husband is the only son in the family, it’s important to know about this Korean tradition and after years of watching and learning and reading, I’ve put together this guide to jesa and written out how to hold jesa in your own home.

Whether it’s Lunar New Year or Chuseok, the Korean Thanksgiving, or if you just want to hold a memorial ceremony for a loved one that has passed on, this will help you. I read this each year before the holidays just to remember and study up so I know where to be and when.

In this guide to jesa, here is what you’ll find:

- Jesa Vocabulary To Know

- Who traditionally holds jesa?

- How To Prepare For Jesa

- How To Perform A Jesa Ceremony

- After Thoughts

(This post contains affiliate links, which means I receive a certain percentage of a sale if you purchase after clicking at no cost to you. Thank you for your support.)

Jesa Vocabulary To Know

Jesa (제사) is an all encompassing term for any memorial ceremony for the dead. There are a few different kinds of rites that fall under the term of jesa (제사) and they include: charye (차례), gijesa (기제사), sije (시제) and myoje (묘제).

- Charye (차례) ceremonies are held on major holidays like Chuseok (Korean Thanksgiving) and Seollal (Lunar New Year).

- Gijesa (기제사) ceremonies are held once a year on the anniversary of the death of the person being honored.

- Sije (시제) ceremonies are held every season.

- Myoje (묘제) ceremonies are held at the grave.

Who traditionally holds jesa?

The oldest male heir of a household holds jesa to honor his family traditionally. This means that my husband, who is an only son, would honor his father and his father’s father when it is his turn to hold jesa.

My husband’s father is still alive so, we go to his house to hold jesa and we honor my husband’s father’s father and his father’s grandfather and his father’s grandfather’s brother because his father’s grandfather’s brother had no male heirs. That’s a mouthful, but basically, it’s a tradition that is traditionally passed down through the male side of the family.

Technically only men are allowed to hold jesa which means that if my husband’s father’s grandfather’s brother had had a female heir, she would not be able to hold jesa for him because presumably she would have married into another family and would be honoring her husband’s family which is how we came to honor his father’s grandfather’s brother as well during our jesa ceremony.

Jesa is passed down through the oldest male heir/relative and that’s the easiest way to remember, put simply. That is also one of the reasons that having a son has traditionally been so important to families. My husband is now the third generation in a row to have only one male heir to carry on the tradition so it is important for him to learn and continue to honor his line for his ancestors. You may have noted that above I kept saying this is how it has “traditionally” been.

If you’re here to know about the traditions and culture, then that’s what you need to know, however, if you’re a female heir or relative that wishes to hold jesa for a loved one or your family, go right ahead. My husband and I have had a daughter and as we don’t plan to have more children and I’m not one to get stuck in technicalities, but do love traditions, this is something we will most definitely be teaching her so that she can hold jesa with her family later.

Holding jesa is about remembering and honoring our relatives and loved one above anything else, so just remember that going forward.

How To Prepare For Jesa

The jesa ceremony has many parts and it’s important to know where to begin. Some things can be done up to a week ahead of time while others should be done just before the ceremony.

The Week Prior

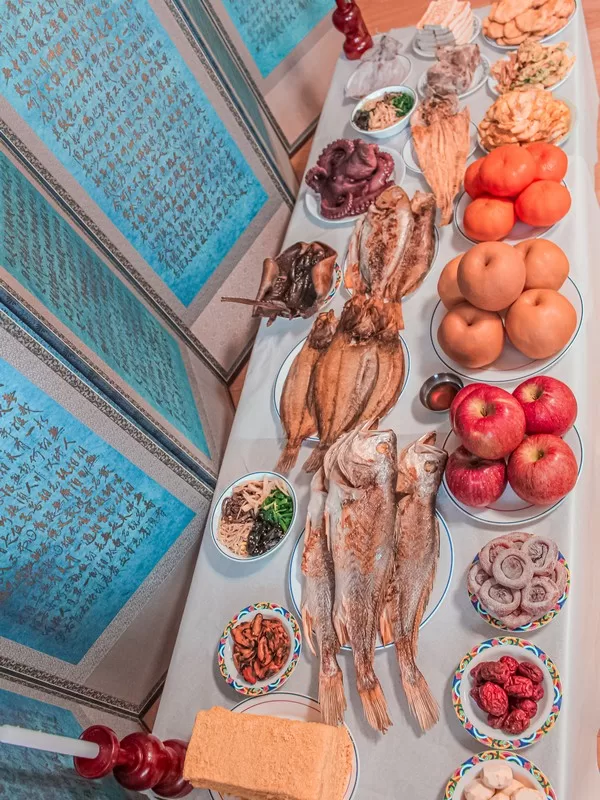

The first thing to do is prepare the various food dishes. This can be done the week prior to the event. Various meats, fruits, and vegetable dishes should be prepared. For us, my mother-in-law prepares this prior to our arrival.

If you’re in Seoul, there is a whole aisle of vendors at Gwangjang Market that specifically prepare foods used in traditional Korean ceremonies. You can pick up quite a few things there. If you’re not sure what to prepare, check out this guide to the jesa table which has all of the specifics.

The Morning of Jesa

We rise with the sun and the first thing to do is be cleansed. I don’t know if this is a hard and fast rule, but in our family, according to my husband, we cannot eat until after the jesa ceremony is completed which is why we wake so early because otherwise we’d be eating way too late in the day.

To cleanse, simply go shower and adorn clean clothes. Think Sunday best or if you have one, this is when you should wear your Korean Hanbok.

Next, you should set the table by preparing the dishes as well as the incense, etc. The guide to the jesa table which I linked to above has all of the specifics on how to set the table. It’s quite specific so it’s important to know which foods go where as some should be on the eastern end of the table while others on the western and so on and so forth.

How To Perform A Jesa Ceremony

The first step is gangsin (강신), or to call the ancestors.

The host of the jesa ceremony called the jeju (제주), in our case my husband’s father, kneels before the set altar to light a stick of incense. This is to invite the ancestors to the table. The jeju’s wife or next of kin then pours a cup of the cheongju (청주), a liquor like sake, and hands it to the jeju who makes a circle over the incense three times and then pours the liquor into a bowl with sand.

The entirety of the cup is poured into the bowl with sand in three pours, that is to say that the whole cup isn’t dumped in at once, instead it is tipped in in three parts. The incense is lit to call the ancestors from above and the liquor is poured to call the ancestors from below.

After the cup has been poured out, it is passed back from the jeju to the person that poured it who then sets it on the table in front of the altar. The jeju rises and bows twice all the way down to the floor to end the first part of the ceremony.

The second step is chamsin (참신), or greeting the ancestors.

Everyone in attendance will bow to the altar two times. Traditionally, men would bow two times while women would bow four, but these days generally everyone bows twice together. Remember, the left hand should always be atop the right hand when bowing down to the floor.

The third step is jinchan (진찬), or serve the ancestors.

The rice and soup are served to the ancestors. You may notice in the pictures that there is no rice on this table. That is because for Seollal, the Lunar New Year, the soup is usually tteokguk, which is a rice cake soup so there won’t be rice served with it.

For Chuseok (추석) there is usually rice served with a soup called tangguk (탕국). Depending on which holiday it is, you may or may not have rice but you will have soup.

You don’t do all of the ancestors in one go, it’s done by generation. In our house we first do my husband’s father’s parents. Their names are written in Hanji and placed in a shinwi or jibang. You can see it pictured between the two candles and furthest back on the table nearest to the screen.

While my Korean family does it this way and each year my husband is in charge of writing out all of the ancestors names in Hanji, many families opt to place a portrait of the person at the center of the table instead.

Some even more traditional families have a shinwi that has the names of the ancestors permanently carved into it and for the rest of the year there are specific rules as to how to store it.

Because the first round is for two ancestors, there are two bowls of soup set on the table at this point in the ceremony and the spoon placed in with the stem to the left as pictured below.

The fourth step is choheon (초헌), or pour the ancestors a drink.

The jeju kneels before the altar and holds a cup with two hands while the wife/next of kin pours the liquor into the cup. The cup is circled over the incense three times and then placed next to the bowl of rice and soup. Another cup is taken and the same thing is done for the other ancestor being honored at the table.

If you are only doing this for one ancestor, then you only do one cup of liquor. The two people stand and walk back to then bow along with the other members twice before once again approaching the table.

Before the next step, the cups are taken off of the table by the wife or next of kin and circled once again over the incense before being poured into a nearby bowl. The cups are then placed back on the smaller table in front of the altar.

The fifth step is aheon (아헌), a second drink is offered.

The procedure is the same as choheon. You are, as stated above, just offering a second drink to the ancestors and doing the bows once again.

The sixth step is jonghun (종헌), a third drink is offered.

The procedure is the same as choheon once again except that this final cup is only filled about 70% of the way. Bow again.

The seventh step is yusik (유식), offering food to the ancestors.

The spoon is placed in the rice bowl sticking straight up with the concave side of the spoon facing east or it is placed in the bowl of soup with the handle end pointing toward the west. Chopsticks are placed on different dishes on the table as if the ancestor would be enjoying that dish especially.

My father-in-law knows what food was especially appealing to his father and is always fast to put the chopsticks on that particular dish on the table. You can do the same. After doing so, once again, step back and two bows follow.

The eighth step is hapmun (합문), allowing the ancestors to partake in peace and quiet.

Technically, everyone except for one person would leave the room. Men would leave out of the east side and face west while the women do the opposite. However, because Korean families are no longer living in traditional Hanok homes with this option, most families opt for a simple moment of silence.

The ninth step is gyemun (계문), the doors are opened.

Assuming you went outside, the descendants wait in silence until the jeju coughs three times to let the ancestors know they are coming back in. But like I said above, we don’t leave the room and just have a moment of silence before my father-in-law coughs quietly to move on.

The next step is removing the rice and soup.

A bowl of water is brought to the table and the jeju takes three spoonfuls of the soup or rice from each bowl and places it into the water as if the ancestors had eaten. In our family, we step back once again at this point and bow twice once again, but according to everything I’ve read, just a moment of silence before the jeju coughs once again is necessary before removing the bowls of rice and soup.

At this point, you move on or begin again depending on how many ancestors you are remembering. If you have just one ancestor, go to the next step, however if you’re remembering more family members like we do, the paper in the shinwi is exchanged for the next pair of ancestors and the table is set again.

We honor my husband’s father’s grandfather and then his father’s grandfather’s brother. We do three rounds total of the third step through the tenth step listed here. Yes, that means triple the number of bows you just counted in the steps above.

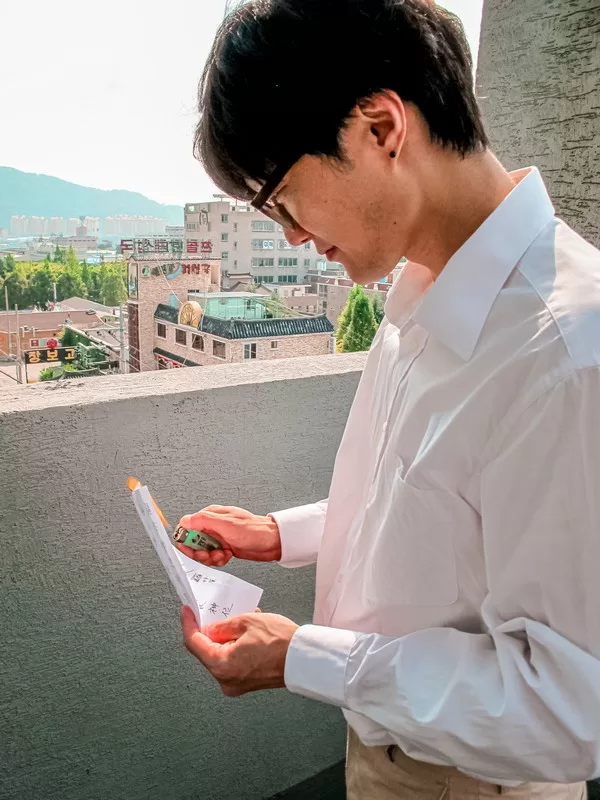

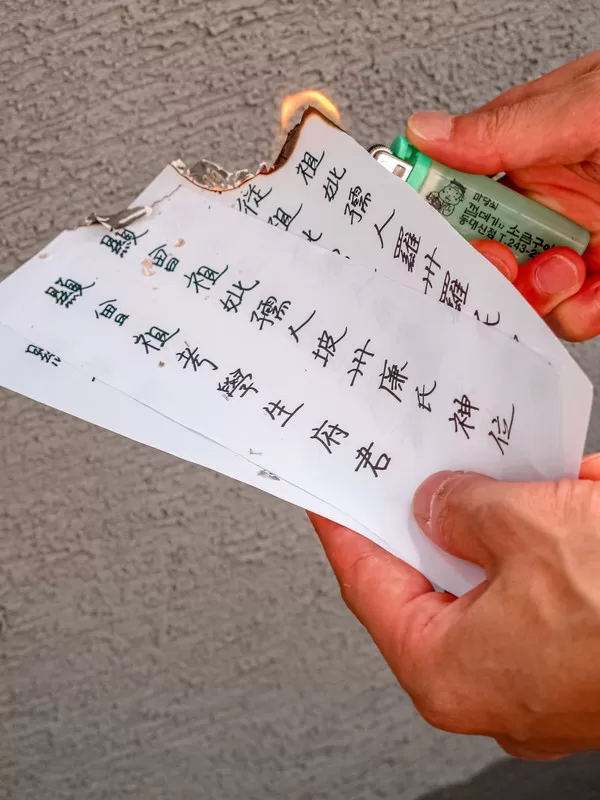

The final step is sasin (사신), or saying farewell to the ancestors.

Everyone would bow as they had during chamsin in the first step. The papers that have the ancestors names written on them are then burned and everyone in attendance sits down to feast on the food.

After Thoughts

It’s best to remember that families are different and with each one comes different traditions and ideas that are passed down. Don’t get bogged down in the rules. The more important thing is that we are together and we are saying thank-you to those that came before us.

Jesa isn’t about worshiping ancestors, it’s about thinking about those that preceded and remembering where we came from. My own grandmother does her own version every year as she places flowers on the grave of her deceased husband back in Ohio. Aren’t we all so much closer than we tend to think?

This is just one of the traditional ceremonies to know when you’re in Korea. If you want to learn more about traditional ceremonies, also learn about the Korean dol and doljabi.

If you’re interested in trying to the traditional Jesa food but don’t have time to wait until Seollal or Chuseok, there are actually restaurants that serve Jesa meals year round. This meal, called heotjesabap, originated in Andong, Korea and if you visit that city you can find restaurants serving up some great Jesa food and then go and visit the Andong sites. Personally, I love the Jesa meal so the first time I visited Andong, I was pretty ecstatic to have this traditional meal option any time of the year. Maybe you will be too.

I hope everyone had a wonderful Lunar New Year wherever they were and that we all take the time to think about our past, our family and where we’ve come to get where we are today.

Did you like this post? Pin It!

13 Comments

Raul Aguirre

MY WIFES JESA CEREMONEY IS BEING HELD IN CALIFORNIA, WHAT IS THE DRESS CODE?

Hallie Bradley

It really depends on the family. In ours, the women wear Hanboks and the men used to wear suits when they were a bit younger. Now that they’re a bit older, they dress up but go a bit more casual, not wearing the jacket. Ideally, you wake up early in the morning, take a shower to cleanse yourself, and then dress up in your Sunday best is how I would go.

Julie

Dear Hallie,

My mother passed away almost a year ago.

Thank you so much for sharing this. I’m not so lost now.

Best wishes,

Julie

Camella

I just started watching Kdrama’s recently and the memorial ceremony keeps coming up in plot lines, so I’ve been reading up on it. Your post made me both laugh (in a good way) and cry. Thank you for posting this information and educating me on this lovely tradition. I’m the family genealogist and my ancestors are very precious to me and this tradition really hits home for me. All the best to you and your family.

Chloe

I presume that my dad’s older brother does this (he lives in Korea), but being in America, I’ve never seen it done in person. Is it okay for me to do a (heavily modified) version of this on my own, or would it be weird (since I’m female, and it’s supposed to be done by men)?

Hallie

I think you can do a modified version that works for you. Some people get caught up in the specifics, but it’s more about honoring your ancestors and if you’re doing that, I believe that’s okay. Also, we have a daughter which means she’ll one day be the one that carries this on in our family. While that may not have been traditionally acceptable, times are changing and again, I believe if your point is to honor your ancestors, then do your thing and be you. I hope the post helps you get ready. There’s another post related to this about how to set the table. Even if you don’t have all of the exact foods it does have some rules about which way to face, etc. so check that out too. ^^

Yong Coi

Hi Chloe,

I came to this wonderful page (Thank you Hallie!) to refresh my memory on how to do a JeSa. I came to England when I was seven so unfortunately, I’m heavily anglicised to the point of ignorance on some aspects of my own culture. I’m preparing to do the JeSa for my mother who passed away exactly a year ago today. It’s not my first JeSa, but certainly the first I will have done by myself.

I wanted to allay any concerns you have for doing this for your ancestors. My mother conducted the JeSa every year, twice a year for as long as I can remember for my grand & great grandparents, so as far as I’m concerned, there are no strict rules to contravene about this being the exclusive domain of the male lineage as long as the intent to honour our ancestors and loved ones are pure.

Before my mother passed, I promised her that no matter what happens, I will always honour her life with a JeSa and regale the rest of my family with stories of her life to keep her in our hearts. It need not be fancy, grand, strict or expensive. Just the act of sharing my life with the dearly departed for one evening to keep her in my heart is good enough. My mother and I used to joke that if I was ever so poor that a grand JeSa was difficult, sharing a packet of ramen and lighting some candles would suffice. My mother was a wonderful woman.

David Chang

Haha, Actually, It’s not easy to explain Jesa (제사) to foreigners. It’s interesting post and help for me. Thanks !

Hallie

That’s exactly why I wrote this. It took me awhile to understand all of the steps myself. ^^

Arran

Korean traditions like this are so fascinating!

It’s really interesting to see how elaborate they are with all the different steps. Seems very unique.

Hallie

They definitely are interesting and unique. Some families have stopped doing them and it’s sad because these are such old traditions that should be held onto I think. I’m glad I can learn these traditions from my family. ^^

Sarah Richards Graba

Thanks for posting this! I’ve been wondering how to actually perform jesa, and it’s impossible to get anything other than a general overview from internet sources (my Korean mother immigrated to America when she was young, so she doesn’t remember/doesn’t have interest in some of the old traditions). Very helpful. Thanks!

Hallie

Thank you for the comment Sarah. I’m glad you find the information useful. It definitely can be difficult to get exact details for some of the older traditions.